The James Hunter Six’s OFF THE FENCE is a landmark album for James Hunter himself for a number of different reasons. In many ways it represents his past, his present and his future.

On the most basic level, the album marks 40 years since the British soul singer made his recording debut with the release of his first album back in ’86. Equally significant is the appearance of one of his earliest supporters and collaborators, Van Morrison.

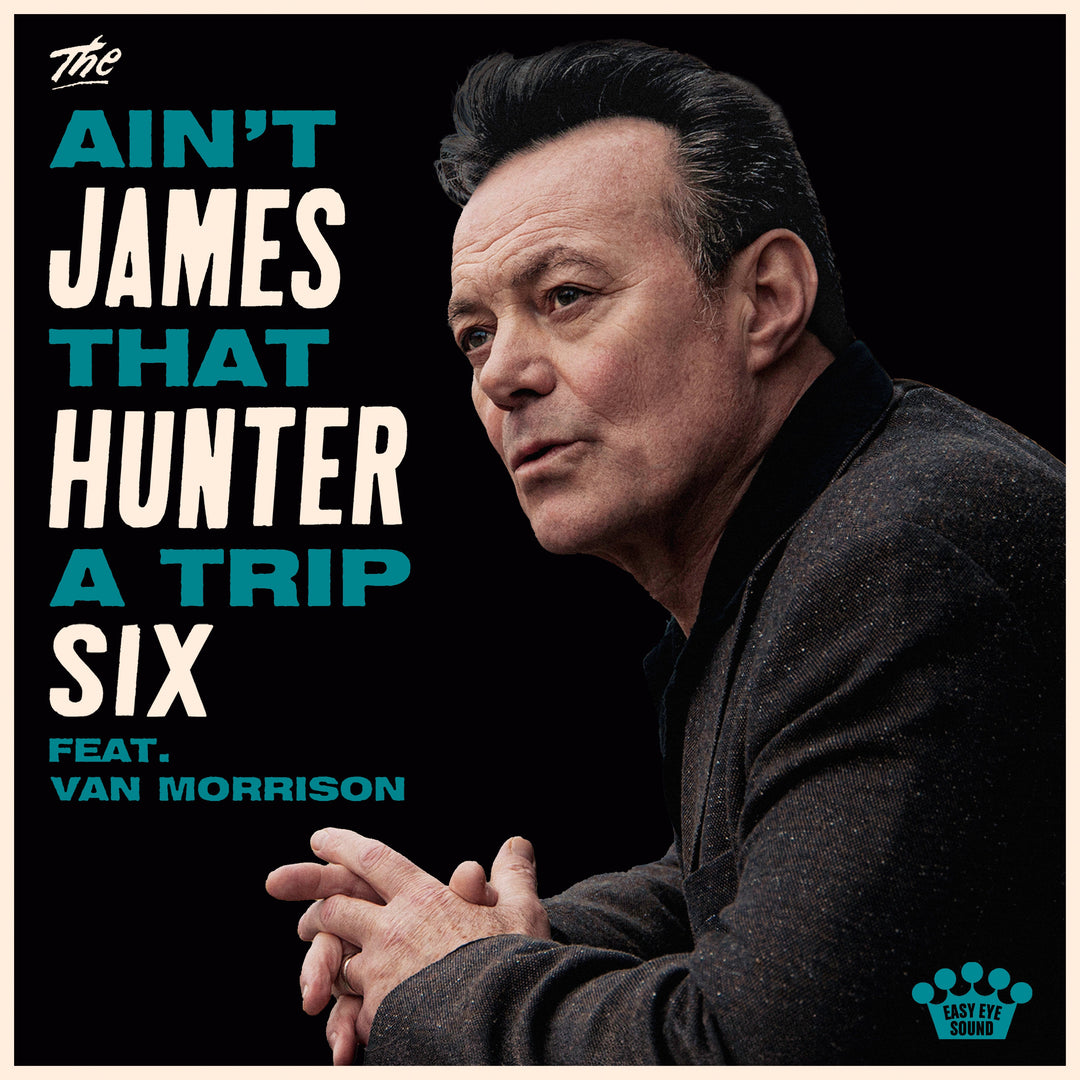

The pair were introduced back in the early ’90s and first collaborated on a brace of Van Morrison albums – 1994’s live set, A Night In San Francisco and ’95’s Days Like This. The following year Morrison returned the favour, guesting on James’s album Believe What I Say, running through a pair of Bobby Bland classics. Three decades on, the legendary 80-year-old Irish singer adds his voice to one of the most joyous tunes on OFF THE FENCE – a jump blues blaster entitled “Ain’t That A Trip.”

“I tried to get Van to sing one of my songs 30 years ago, but I hadn’t really written anything he fancied at the time,” recalls James. “But we were having a chin wag backstage at a gig where we were opening, and I asked him if he wanted to sing something on our next record and he said yes, so I sent him the track. Hearing him actually singing words I wrote gave me a real kick. It’s brilliant.”

The raucous party tune sits among the 12 self-penned gems that make up OFF THE FENCE, all of which are delivered with the Hunter’s customary blend of smooth vocal control coupled with heart-worn grit and wit.

Hunter’s own musical journey started 66 miles from London in Colchester, Essex, where he was born in 1962. His life-changing moment came at the age of nine when his grandmother handed him her Dansette record player and a collection of old 78s. Included in that pile of shellac was a copy of Jackie Wilson’s 1958 hook-filled hit, “Reet Petite” – a tune that musically helped transform R&B into soul. It proved equally as transformational as far as young James was concerned, providing him with a gateway to a whole new musical world that seemed a million miles away from 70s Winter of Discontent Essex.

By the time he’d reached his teens, Hunter had discovered a further set of musical heroes - Ray Charles, Dee Clark, Sam Cooke, Lowman Pauling, T-Bone Walker and Howlin’ Wolf among them. Having picked up the guitar, he left school and signed up to work on the railways in a quest to enhance his own blues cred.

“I thought that's the perfect background, and I picked it for that. At the age of 17, I thought, yeah, that's like a Muddy Waters back story. But if I'd passed all my courses and paid attention when they sent me to West Ham College, then my songs would all be about being a senior rail technician and the picturesque aspect may have been slightly lost," he laughs.

Armed with his self-deprecating sense of humour, Hunter admits that British Rail’s loss was music’s gain. Heading to London, he gravitated to Camden Town where clubs like Dingwalls and record shops like Rock On provided a safe haven for those unenamoured with modern day pop music. The latter shop was run by Ted Carroll who had also set up Ace Records – the pre-eminent label for soul, rockabilly, rock’n’roll and R&B reissues in the UK. The bequiffed Hunter fitted in perfectly on the Ace roster.

Using the tongue-in-cheek moniker of Howlin’ Wilf And The Veejays, he and his four-piece band released their aforementioned debut album, Cry Wilf!, on Ace Records in 1986. Listen back to that long-player now and it’s immediately clear that Hunter’s musical approach and vocal style were already fully formed before he’d even hit his mid-20s. It wasn’t long before the majors – or rather their cooler subsidiaries – came knocking. But Hunter was and never has been flavour of the month. Nor has his chosen path ever been obvious or easy.

Despite his increasing profile, the early 2000s proved problematic for the singer. There were times when day jobs beckoned and busking seemed more lucrative than recording and touring. About to turn 40, he was told he was simply too old to get signed to a proper record deal.

“I did ask them what they expected me to do about that and, looking back, it’s a bit worrying because that was over 20 years ago! But I’ve reached a point now where age is an advantage because people think you’ve acquired some kind of wisdom but, nah…”

Undeterred, James knuckled down and delivered his most impactful work to date: People Gonna Talk. Recorded in 2003, it took three years for the album to hit the racks, such were the issues in finding a label willing to release it. When Nashville indie label Rounder Records finally stepped in, the album scored a GRAMMY nomination and topped the Billboard Album Blues Chart for six weeks (its successor, 2008’s The Hard Way, would also hit the top slot). As his profile started to grow Stateside, so too did his audience. Slots playing with Aretha Franklin, Willie Nelson and Etta James followed.

“I think when people over there heard what I was doing it was quite a novelty,” reflects James. “Before they heard me speak some people thought I was an old Black guy from way back. Afterwards they thought, ‘How can he sing like that when he can’t even talk properly!’. But when things started to happen in America for me, then word filtered back to England too.”

For all his US popularity, Hunter is a distinctly British artist whose conversations are still peppered with talk of the comedians, politicians and cultural figures from his youth as much as they are with musicians or key 45s. Humour, he admits, is a handy shield and vital to how he views the world.

“Even when I write love songs, I tend to put an element of British sardonicism in there,” he admits. “I don't want to get too sort of chocolate boxy with my material. Even if you’re saying sweet stuff I always have to put a joke in there or something that makes a point or twists things a bit.”

“‘Particular,’ one of the songs from the new album, is like that,” he continues. “saying ‘it’s a lovely day if you’re not particular’ is a typical dour North East Essex turn of phrase. As a song, it’s the equivalent of the joke about the Yorkshireman treated to a Bob Hope concert. Everyone around him is erupting, and at the end someone asks him if he enjoyed it. He answers: ‘It were alreyt for them as likes laffin’.” That’s where I was coming from: trying to write something from the “Great American Songbook” but with more of a British sensibility.”

In many respects Hunter is part of a great British musical tradition that probably stems from music hall and then moves forward to London in the ’60s – a vital period when Soho was a musical hotbed and Georgie Fame And The Blue Flames were the house band at The Flamingo. Like Fame – the keyboard player and singer with whom Hunter would play during his ’90s stint with Van Morrison - James finds inspiration from Black American music in a very specific way.

“Georgie Fame is one of the few British artists that is more about the groove and the feel than anything else,” nods Hunter. “A lot of people who drew on Black music – like The Stones - went for what they perceived as the aggression they heard in the music, but the groove is what really sold Black music to me.”

A man who has always been drawn to the power of a single song rather than full albums, groove and feel are still what define Hunter’s approach to music now just as they always have. That said, his lyrics express a deeper set of universal truths based around matters of the heart – something which he himself would never describe in those terms.

“What I write about is real life, but it’s not necessarily my own real life. Sometimes you take other people's experiences and you write vicariously through them. It’s like Tony Hancock said: ‘You don’t have to fall off a cliff to know it hurts.”

Indeed, OFF THE FENCE is full of examples of Hunter’s ability to translate the everyday into something that works on a deeper emotional level. You can hear it on the album’s opening track, the rolling rumba of “Two Birds With One Stone.”

“My wife Jessie was on the phone to her old piano teacher, and he just happened to use the phrase. I thought it sounded good, so I grabbed my notebook and it looked even better written down. Usually, it’s a phrase used positively –as in, saving time. But I thought, why not use if in a negative sense and write something about destroying two lives with one thoughtless remark,” he explains.

Elsewhere, the infectious, twin-horned roll of “A Sure Thing,” the first track to be released from OFF THE FENCE, further showcases Hunter’s word play at work.

“I thought the title was a nice phrase and, musically, I was trying to get a bit of Northern Soul in there - which is where we’re trying to appeal to people’s feet. But, lyrically, it’s just a different way of reflecting on somebody saying that they want to play things safe.”

“The way I write is what I call the Thesaurus method. I take the salient words describing the subject of the song and try to find as many synonyms for them as I can and then look for stuff to rhyme them with. As annoying as it is to admit it, there’s a lot of work goes into the phrasing, and I make a lot of demos at home to get that side of it right.”

If phrasing is important to Hunter, so too are musical textures. The James Hunter Six – who, alongside James, also include Myles Weeks (double bass), Rudy Albin Petschauer (drums), Andrew Kingslow (keyboards, percussion), Michael Buckley (baritone saxophone) and Drew Vanderwinckel (tenor saxophone) – are masters of their craft and have developed a near-telepathic relationship with their leader. The album is full of examples of their innate understanding of the music and the needs of each song.

Arguably the most beautiful tune on the album is “Here And Now,” which also showcases Hunter’s own ability to conjure up his own musical atmospherics as a guitar player, his lilting, evocative fretwork recalling the great instrumentalists of the ’60s – British legends The Shadows among them.

“Well, it’s the first time I’ve had a guitar with a Bigsby [tremolo] so I had to put it to good use.” says James, explaining his haunting guitar part. “Hank Marvin described his playing rather modestly by saying ‘When I run out of ideas, I give the tremelo a little shake.’ I tried to use the same technique; to use something subtle on what is quite a delicate song – I gave it a shake. That said, that was one of the easiest songs to write on the album. It practically wrote itself.”

If OFF THE FENCE is the perfect amalgam of everything that is great about James Hunter’s songwriting, delivery and outlook, it also marks a fresh start.

His eleventh studio album, it is also his first release on Dan Auerbach’s Easy Eye Sound label following a thirteen year-plus relationship with Daptone Records (home to Sharon Jones And The Dap-Kings, Charles Bradley and Thee Sacred Souls). With the album produced once again by Bosco Mann (aka Gabriel Roth, Daptone’s co-founder), Hunter is keen to point out that the label switch was purely down to circumstances.

“Artistically and personally, working with Daptone has been such a great fit for us,” explains Hunter, enthusing about his relationship with the label and with Roth in particular. “I know what it’s like talking to yourself because of my conversations with Gabe. We always end up interrupting each other because we’re always about to say the same thing, and it ends up being a race for who gets to say it first.”

Such is James’s relationship with Gabe that it was Roth who agreed Easy Eye Sound would be a suitable home for his friend’s next album. James’s first encounter with Dan suggests that Gabe was right.

“I met Dan in the studio when we had some more overdubs to do and his enthusiasm was very encouraging” says Hunter of The Black Keys frontman. “He was dancing around a lot while he was listening to the stuff and really digging it. He knows what I’m going for, and he had that understanding about my stuff that made me feel we were in good hands.”

Taste matters to James Hunter. And, even after all this time, so too does music. Now more than ever, in fact. OFF THE FENCE is proof of that. While he is too modest to say as much, the album is collection of tunes built around a profound understanding of love and of life itself.

“Music is still a visceral thing to me. The groove and the melodic stuff still gets me excited. It’s hard to explain exactly what it does to me,” reflects the singer, admitting that he remains on a musical quest of sorts. “But I’ll hear a piece of music on the radio and I’ll be envious of it, so I’ll try and write my version of it, to catch the feel of it, and to hope that what I’ve written to affects me in the way that the original did.”

“My wife bought me a book about the songwriters who worked in the Brill Building in the ’50s and ’60s – Goffin and King, Leiber and Stoller, Pomus and Shuman, people who were a big influence on me. They sat in their cubby holes and wrote songs that really affected people. That’s my sort of fantasy life. Not being on stage or in a studio, but being locked in an office with an ashtray and a piano.”

And with that, James Hunter – a man who does indeed write songs that really affect people - leaves us with one of his typical one-liners…

“Trouble is I’ve given up smoking and I can't play piano…”

Read More